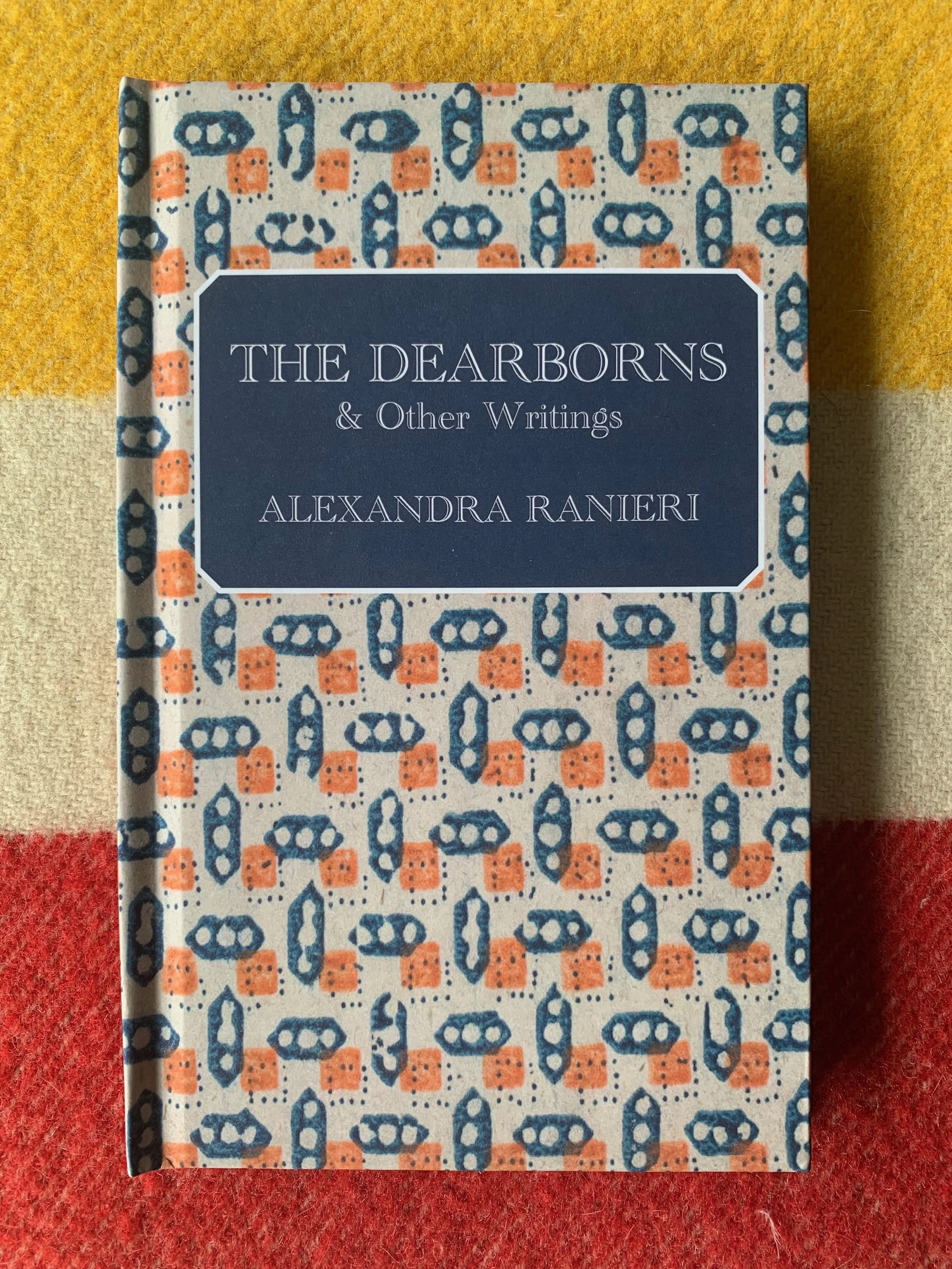

The Dearborns & Other Writings: Available March 1

Editor’s Note: The Dearborns & Other Writings by Alexandra Ranieri is now available for purchase. Click below to buy your copy today.

Alexandra Ranieri’s second book, The Dearborns & Other Writings, will be available to purchase from March 1. With this collection of short works, Ranieri wrestles on a more intimate footing with the themes of natural wonder, personal hubris, and the restorative power of compassion, which have informed her novels and plays. In the title story, “The Dearborns”, we are thrust into the deeply personal story of one family’s self-destruction, fueled by secrets, lies and revenge, while “The Golden Web” follows a tapestry weaver’s slow descent into madness. With the light-hearted “The Lovesick Maiden”, Ranieri paints a lively portrait in miniature of the Golden Age in Amsterdam. In her “Passages”, short meditations on everything from minute wonders of the natural world to foibles of human nature, the reader is invited to explore new perspectives on the everyday, while her tight, formally resonant verse recalls the musicality and artistic virtuosity of a bygone era. This is a volume sure to please anyone who looks to be caught unawares and delighted by the power of language.

Please enjoy this excerpt from the volume’s title story, The Dearborns.

The Dearborns

It was to be the last really fine day in Chicago that November; and the front room of the Art Institute’s Impressionist wing was full. Suffused with light in every corner, the room’s paintings reflected back onto eager eyes their delusion of summer; fashionable Parisians from a century ago lounged in bathing costumes on the banks of multicolored rivers, or sat singing at the piano, or dined al fresco, on balconies of restaurants long since shuttered. Only the grand centerpiece of the room, the Rainy Day, remained stolidly true to its name—forever in shade, its inhabitants lived on in a gray and black landscape, relieved only by one lady’s blush, her bright pearl earring.

The security guard, a short, wizened Black woman of seventy or beyond, still marched back and forth, only stopping to listen to two friends arguing over Rodin’s Balzac.

“It seems very cruel to me,” the young man said, “Look, he’s caught him at his most vulnerable point—it’s as though Rodin’s laughing at him.”

“No, no, no,” the girl responded, unreasonably incensed, “You’ve got it completely wrong. Just look at his jaw, the way it’s set. Rodin has perfectly captured his mixture of bravado and embarrassment.”

“That’s right,” emerged from the Sybil her verdict; for, beyond security guard, she was also, beyond doubt, the guardian of every secret of every work in this room, her favorite and most frequent beat. She, too, became animated, and with expansive gestures continued, “Balzac, in fact, said this was his favorite portrait. It was completed near the end of his life—and what a life! He wrote hundreds of books, but died without a penny. Oh, yes, doubtless, he felt great embarrassment at this time of his life, though he had begun so sure of success.”

The two friends, enchanted, listened with the utmost attention, the girl evincing almost too much pleasure at being proven right. After some further discussion, they thanked her and drifted away, into the anonymity of the crowd. The guard—Millie—returned to her beat, and it would have seemed to anyone there she gave no thought to the people coming and going; that, much like the patrons, she was present solely to appreciate Art. But a more careful observer might have noticed her glance tending, again and again, in one direction, and might have followed this glance at last to a hunched figure, sitting alone and seemingly without much awareness of his surroundings, on one of the two benches at the front of the room.

It was a young man, in shabby light blue jeans, a maroon sport coat, and dirty sneakers—and he, by contrast to Millie, seemed only aware of the other people in the room, without any interest in the paintings. He glanced furtively here and there, at different faces, now and again, and when he did by chance land on a painted face, his own seemed to go blank, his expression, and with it his self, to disappear—until he tore his eyes away again, and focussed instead on the floor, or some insignificant person.

It became clear to Millie that he must be waiting for some significant person; but it was already a long time that he had sat there, and she wondered, will he still be sitting there at closing time? A young woman pushed open the door nearest the bench; a beautiful girl, in a maroon coat of very different description—it seemed to Millie to be made of good quality wool, and round her neck was wrapped a white cashmere scarf, neatly tucked in. She looked at the young man, who had not turned at her entrance. Was it possible, that these two—but no, the girl leaned forward, smiling, and the young man did catch her eye, without recognition.

“I’m so sorry,” the girl said, “may I sit here?”

The young man had been in the center of the bench—he hastily budged, without speaking, and almost without looking at the girl as she sat.

“Thank you,” she said, and began to wait, too—but her eyes lingered long over several different paintings, with evident love, of which love Millie approved. Of this girl in her entirety she approved. Her beauty was of a full, rich kind—her thick, dark hair hung in a rope down to the middle of her back, her dark eyes were at all times full of whatever emotion most took pervaded most the moment, and her lips and cheeks were pink with unfeigned youth. She was, in short, a perfect Sargent—and what a contrast, between this doll, who might get the good graces of just about anyone with a look, and her accidental companion! Millie looked at him again with some private distaste. To be sure, he might’ve been handsome, had he worn better clothes, and a better expression—but as it was his jaw seemed perpetually clenched, and his own dark hair hung round his ears, catching the edge of a badly maintained scruff. He seemed to be one of those with a grudge against the world for having brought them about—and Millie, having brought herself through a difficult life with some good grace, found such an attitude unbearable.

As Millie watched, the man seemed to come to the end of his tether—with a sudden curse, which startled the girl, he stood up and headed towards the door. It was at this moment the girl caught sight of a lean, middle-aged man coming in from one of the other galleries—her face lit up, she stood, and said, “Uncle Robert!”

“Anna!” Uncle Robert said, but his eye remained, even as they embraced, not on his niece, but on the young man. He had turned back from the door, and stared at the older man with a mixture of anger and hesitation, as though he could not quite make up his mind to do something—but when Uncle Robert cast on him a bland, thin smile, the hesitation disappeared; the young man came quickly up to him, even closer than Anna, who frowned at him in her confusion. But the young man ignored her.

“I’ve been waiting for you,” he said, in a low voice.